Implementation

Before reading our recommendations, consider the following thought experiments:

- If you were incentivized to increase the average life expectancy of a defined population of patients, how would you redesign your practice, health system, policies, or funding priorities (depending upon your role in the healthcare system)?

- If instead you were incentivized to maximize the average quality of life of a defined population, how would you redesign your practice, health system, policies, or funding priorities?

- What if you were incentivized to optimize the cognitive, social, and moral growth and development of individuals in your defined population assuming such development could be measured?

- How would you assure that everyone in your defined population experienced the best possible death experience?

- Finally, how would you help people in your defined population clarify the tradeoffs they were willing to make between and among those outcomes?

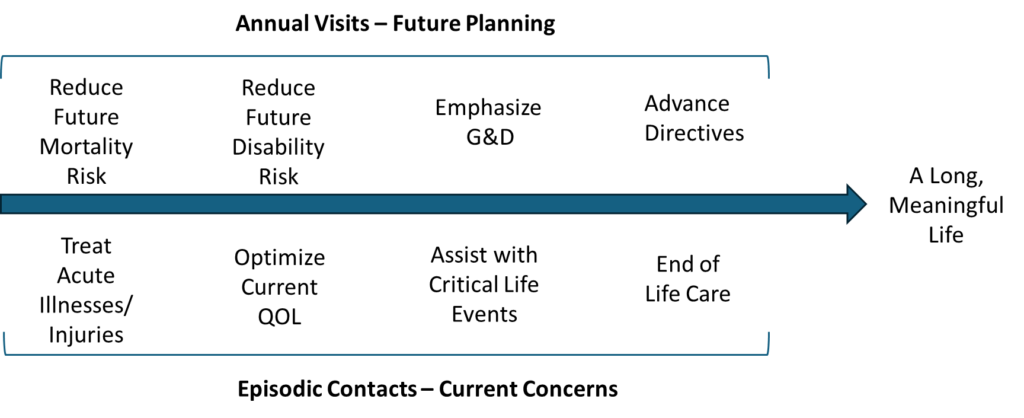

While goal-oriented care is based upon a simple concept, it is not the way most clinicians have been trained to think. It requires a different mindset. And because patients have also become accustomed to disease-oriented thinking, they too have to adjust. One place to begin is to consider when each of the four goal types could best be addressed. It turns out that each goal type involves both episodic care and long term planning.

Future-oriented goals such as prevention and advance planning are best addressed during annual comprehensive visits. In contrast, urgent goals like treating life-threatening illnesses or managing end-of-life care require more immediate attention (see below).

Three Step Process

Conceptually, goal-oriented care involves a sequence of three steps, connecting, co-creating, and collaborating.

Connecting includes clarifying goals, values, and initial thoughts or concerns about possible strategies. Co-Creating is the process during which participants—patients, families, and healthcare team members—come to a shared agreement on goals, objectives, and strategies. Collaborating involves assigning tasks and responsibilities to ensure the successful achievement of those goals. The result is an action plan, not unlike those used for asthma but including when, how, and with who to follow-up as well as the tasks assigned to healthcare team members.

For each goal type, the steps remain the same, but the details differ.

Prevention of Premature Death and Disability

Prevention of future adverse outcomes generally requires a comprehensive assessment of risks and assets and an analysis of the relative benefits and harms of various mitigation strategies. This is best done at an annual preventive care visit. Most of the required information can be gathered by asking patients to complete a pre-visit questionnaire and from the medical record.

Because of the increasing complexities involved, the analyses will ultimately benefit from computer algorithms and better information on the actual causes of death and disability and the impacts of mitigation strategies (see Case #7 below). However, it is often clear which interventions would be most impactful (Se Cases #1 and #2 below), and, if not, standard recommendations generally apply.

- Mold JW, DeWalt DA, Duffy FD. Goal-Oriented Prevention: How to Fit a Square Peg into a Round Hole. J Amer Board Fam Med, 2023; 36: 333-338. https://www.jabfm.org/content/36/2/33

Improving Current Quality of Life

Improving current quality of life begins with clarification of what quality of life means to the individual. The focus is usually on essential and desired activities and relationships (See Case #3 below). Helpful questions include:

- How are your symptoms impacting your life and the things you need and want to do?

- What do you hope to be able to do once we get your pain under control?

- What does a typical day in your life look like? What tasks and relationships are giving you the most trouble (See Case #4 below)?

- What would you like to be able to do that you can’t do now?

- What are the activities and relationships that mean the most to you?

It is sometimes helpful to also ask about underlying values by asking why a desired outcome is important.

- Jennings LA, Mold JW. Person-Centered, Goal-Oriented Care Helped My Patients Improve Their Quality of Life. J Amer Board of Family Med, 2024; 37 (3): 506-511

Optimizing Personal Growth and Development

Because patients rarely seek help from healthcare professionals with personal growth and development, the usual approach is to ask age-appropriate questions based upon established developmental models (Erikson, Deci and Ryan, Solberg) and to engage with professionals and community services tasked with helping people who are having difficulty. (See Case #5 below.)

Ensuring a Good Death

Helping individuals achieve a good death involves determining when to discontinue life prolonging measures, clarifying end-of-life values and preferences, identifying and instructing a surrogate decision maker, and documenting and disseminating specific restrictions and requests. These conversations should begin in early adulthood and be revisited annually. Helpful questions include:

- What conditions, if permanent, would you consider worse than death? That is, if you were in that situation, and it wasn’t going to improve, you would not want me to give you antibiotics for pneumonia (See Case #6 below).

- If you were no longer able to make decisions for yourself about health matters, who would you want to make decisions for you? Have you discussed your preferences with them?

- At the end of life, which would be worse for you, to be in pain or to be unable to think clearly?

- Do you believe that food and fluids should be provided to everyone until the very end, or would it be okay to die without artificially administered food and fluids when you are no longer able to consume them on your own?

- Are you willing to undergo an autopsy after death if it might be of help to your family, your physicians, or medical science?

Course Corrections

Note: There is actually a fourth step, Course Correction, which can be extremely important. Very few plans proceed as expected, and a great deal can be learned when they don’t. Adjustments to the original plan should be expected.

Case #1: Mr. De Silva

Mr. De Silva is a 68-year-old retired welder. Since his wife died 5 years ago, he lives by himself in a one bedroom apartment. He requires supplemental oxygen 24 hours a day because of emphysema. However, he still enjoys his somewhat limited life, which includes reading, television, e-mailing friends, and going out to eat twice a week at a cafeteria close to his apartment building. His two children and four grandchildren come to visit him once a week. He quit smoking several years ago, has had the most recent influenza, RSV, and pneumonia vaccinations, and correctly uses the maintenance and rescue inhalers recommended for his emphysema. One of Mr. Sawyer’s primary goals is to stay alive as long as he is able to enjoy being with family and friends.

Problem-Oriented Approach: His physician checks his pulse oximetry on and off of oxygen and obtains an FEV1 measurement to monitor the severity of his disease. She checks his complete blood counts to make sure he is not anemic and to see if he qualifies for treatment with a medication to inhibit eosinophils and obtains a chest X-ray to see if there are any areas that might suggest a surgical treatment. She commends Mr. Sawyer for his adherence to the inhalers and oxygen and for getting the recommended immunizations.

Goal-Oriented Approach: His physician advises him that the preventable conditions most likely to cause his death are a lung infection or serious injuries from an accidental fall. She advises him to brush his teeth several times a day and have his teeth cleaned by a dental hygienist every 6 months to reduce the number of pneumonia-causing bacteria in his mouth. She suggests that he wash his hands after getting his food in the cafeteria or after contact with public surfaces and to tell his children not to visit when they have a cold or the flu. Because there is evidence suggesting that medicines that reduce stomach acid may increase the risk of pneumonia in people with chronic lung disease, she gives him a list of those medications to avoid. In addition, she reviews his diet and suggests a daily multivitamin to insure that he is getting the vitamins and minerals needed for his immune system to function optimally. They review the potential need for a respirator should he have a serious exacerbation of his lung disease and decide against it unless there is a reasonable likelihood of recovery. They also discuss fall reduction strategies.

Case #2: Mrs. Baxter

Mrs. Baxter is a 53 year-old African American mother of three and grandmother of 8. Her medical problems include diabetes, high blood pressure, and arthritis. During a recent office visit her family doctor said to her, “You still seem to be enjoying life,” to which she replied, I definitely am.” Her doctor then said, “I assume that one of the reasons you come to see me is so I can help you stay alive as long as possible.” Again she answered in the affirmative. Then her doctor asked her, “What would you still like to see and do before you die?” She began talking about her grandchildren, family gatherings, graduations and marriages. Then her doctor asked, “What do you think would be the single most important thing you could do, with my help, to increase the chance that you will live long enough to see those things happen?” She said, “I should probably stop smoking.” Her doctor agreed, and she said, “I’m going to do it.” And she did.

Encouraging Mrs. Sawyer to focus on her goal caused her to become invested in a strategy to achieve it. And it was a strategy that she herself chose. In the traditional problem-oriented approach, smoking would have been identified as one of Mrs. Sawyer’s problems, and she would have been advised to quit. The difference between a goal-directed approach and a problem- oriented one may seem subtle, but it is actually huge; it is the difference between a positive, collaborative approach (i.e., achievement of a goal endorsed by the patient) and a negative, directive one (i.e., correcting an abnormality identified by the doctor). The positive approach is almost always more effective because it leads to a greater motivation and investment, which almost always leads to greater returns.

Case #3: Mr. Johnson

Mr. Johnson was a 31-year-old architect. At the insistence of his wife, he made an appointment with her primary care doctor to discuss a shoulder problem he’d had for more than a decade. His sports career had been cut short during high school because of an injury to his shoulder. Since high school, he had continued to experience intermittent pain, and he had seen several other primary care doctors, an orthopedic surgeon, and a physical therapist. He had tried rest, heat, and ice, a variety of exercises, an injection, and anti-inflammatory medications, each of which helped but only temporarily. The orthopedist had offered an operation, but he said that he couldn’t guarantee the result and the recovery period would be burdensome.

The new primary care doctor took a different approach. He asked, “How does the pain affect your life? What does it keep you from doing?” Mr. Johnson replied that the most important thing he was unable to do was to hunt deer with a bow and arrow, a hobby he had shared with his father and brother prior to the shoulder problem. Then he said, “You know, I’ve seen some deer hunters using crossbows. I could probably do that, but to get a crossbow license I think I would need a doctor’s note saying that I am not physically able to use a traditional bow.” His doctor wrote the note, and soon Mr. Johnson was enjoying hunting again.

Case #4: Mrs. Lindsey

Mrs. Lindsey was an 80-year-old retired teacher who was living independently in her own home. Dr. James became her primary care doctor when her prior doctor moved to a different state. He had been evaluating her for weight loss and some abnormal liver tests. As part of his usual approach, Dr. James asked Mrs. Lindsey to describe a typical day in her life. She said, “I get up quite early, around 6AM, go into the bathroom, wash myself off with a washcloth, and then get dressed. Then I spend the next half-hour or so trying to get my socks and shoes on.” Of course, Dr. James stopped her at that point and asked her why it took so long to put on her shoes. She said that she wasn’t able to bend far enough forward to reach her feet easily without stretching, bouncing, and struggling because of the arthritis in her hips and knees.

Dr. James referred Mrs. Lindsey to an occupational therapist, who, in one 45-minute session, taught her how to use a sock donner and a long-handled shoe horn. With those two inexpensive pieces of equipment, she was able to comfortably finish dressing in about five minutes. The problem-oriented approach to Mrs. Palmer’s arthritis would more likely have unfolded in one of the following ways. Since she was not complaining of any pain, it might not have been addressed at all. If she had mentioned stiffness or trouble walking, her doctor might have ordered X-rays and lab tests, which would have confirmed the diagnosis of osteoarthritis. Management might have included Tylenol or an anti-inflammatory medication, injections, measures which would not have improved the quality of Mrs. Lindsey’s daily life very much, certainly not as much as the adaptive equipment did.

Case #5: Mrs. Monson

Mrs. Monson was a fifty-six-year-old woman who came to see her new physician for an initial visit complaining of diffuse body aches that sounded more muscular than arthritic in nature. She looked tired and somewhat depressed. The rest of her history and her physical examination were unremarkable. As they talked, she revealed that she lived with her husband and twenty-six-year-old son. The son’s failure to launch was clearly of great concern to both she and her husband and they had been arguing about how to handle the situation. Her husband favored giving their son a deadline for moving out regardless of any obstacles he might face. She was reluctant, worried that he wouldn’t be able to manage on his own.

They went on to discuss her understanding of her overall goal as a parent, the developmental challenges involved in her son’s quest to become independent, and her need to move on to the next phase of her life as well. The conversation took about ten of the twenty minutes. Her physician ordered some blood work (CBC, ESR, CPK, and 25-OH Vitamin D), and asked her to return in a week. All of the lab test results were normal. When she returned a week later as planned, her entire appearance had changed. She was bright and even somewhat cheerful, aches and pains gone. She relayed that she and her husband had agreed to give their son one month to move out, he had consented, and she felt good about the decision. They had a brief discussion about what she would do if the son failed to make necessary arrangements.

Case #6: Mrs. Moody

When Dr. Brown first met Mrs. Moody, she was 70 years old. She came to his office accompanied by her daughter who reported that her mother was experiencing problems with her short-term memory. Testing revealed that Mrs. Moody’s short-term memory was moderately impaired, but that her judgment and decision-making abilities were fine. During a review of the pre-visit questionnaire the two of them had worked on together, Mrs. Moody said she definitely would not want to be kept alive if she was no longer able to recognize members of her own family but was willing to be treated for pneumonia and other treatable conditions until that time.

Three years later, because her thinking ability had continued to deteriorate, Mrs. Moody was admitted to the memory care unit of a nursing home. After being there for a year, she was no longer able to recognize her daughter, who had been visiting her daily since her admission. At that point her daughter reminded Dr. Brown of her mother’s directive. Dr. Brown advised the nursing home staff and medical team that life prolongation was no longer a goal. He told the staff to stop measuring her vital signs, and he discontinued her medicines.

Two months later, Dr. Brown received another call from Mrs. Moody’s daughter. She asked, “Why did you write orders for a pneumonia shot for my mother? Doesn’t that directly contradict her directive?” While handling the mountains of paperwork that came across his desk each day, Dr. Brown had signed a number of routine pneumonia vaccination orders that week – hers included – without even thinking about it. He apologized. Mrs. Delaney died peacefully a couple of months later with her daughter by her side.

Case #7: Use of predictive algorithms.

Estimated gains in life expectancy from a variety of preventive strategies, based upon the predictive algorithm developed by Taksler and colleagues, for a sedentary 55 year-old white married man, a 1 pack per day smoker who consumes 4 cans of beer per day. BMI: 30, BP: 160/90, LDL cholesterol: 160, HDL cholesterol: 38, triglycerides: 200, A1c: 8.5%.

| Preventive Strategy | Estimated Months of Life Gained |

| Smoking Cessation | 96 |

| Moderate Physical Activity | 31.2 |

| Healthy Diet | 19.2 |

| Reduction to 1 beer per day | 19.2 |

| High dose statin or LDL-C reduction to 100 mg/dl | 12 |

| BP reduction to 130/80 | 9 |

| A1c reduction to 7% | 2 |

| Colonoscopy (every 10 years) | 4 |

| Lung CT (annually) | 2 |

| Influenza vaccination (annually) | <1 |

Caveats

- Using the word “goal(s)” in conversations with patients is rarely necessary or helpful. The term carries multiple meanings and can feel overwhelming for some individuals. Instead, it is more effective to ask the types of questions suggested above and then clearly express your understanding of what the patient hopes to achieve. When it is necessary to use a word to describe the process, the word “priority(ies)” often works better.

- Understanding a patient’s values is nearly always helpful, but it becomes especially so when a goal initially seems unrealistic. For instance, if a patient wishes to own a dog but is restricted by their landlord, exploring the reasons behind this desire can reveal alternative options.

- It is not usually necessary to create a formal goals list or to use a weighting mechanism (e.g., goal attainment scaling). It is generally sufficient to clarify the desired outcomes in encounter notes and, of course, referral letters.

- In goal-oriented care, the terms “non-compliant” and “non-adherent” are meaningless and irrelevant. When a plan doesn’t work as expected, lessons are learned, and the plan is revised. Readjustment of plans is an expected part of the process.

Implementation Guide

This Implementation Guide was developed in collaboration with a network of private primary care practices in Colorado called ART2.